Pithy Wisdom from Two World War II Veterans on Veterans Day

Today is Veterans Day, which honors military veterans who have served in the US armed forces. I want to especially honor the many members of my family who have served, notably: My father (see below), my mother, who was a nurse and Lieutenant in the US Army during WWII, our son (see below), and my father-in-law Alden Eaton, who served in the Philippines as an officer and artillery spotter.

Our son Chris recently became a veteran after serving for nearly 14 years on active duty in Air Force Special Operations as a Pararescueman (combat search and rescue). He went on multiple combat deployments. Thank you Chris for your service!

My father, Dr. Raymond Sobel, was a Major in the US Army and apparently spent more days in combat than any Army physician in the European theatre. The rest of this newsletter is drawn from one I published in 2009, after visiting him and discussing his wartime experiences. He had pulled out an envelope he had prepared and asked me to give it to our son Chris, who had recently returned from a combat deployment abroad. It contained letters he had sent home during the war and several photographs of him during the bloody Italian campaign of 1943-1945, during which there were 320,000 allied casualties including 50,000 dead. It was the most lethal campaign in the World War II European theater.

My father considers himself extraordinary lucky: He survived several years of ferocious combat as a front-line medical doctor in Italy with the US Army’s 34th infantry division. While many others died, he survived. He survived landing at the beach in Salerno, Italy, while under fire; the second wave at Anzio, north of Rome, under worse fire; Monte Casino, where, he will tell you grimly, his battalion started with 30 officers and was left with only five standing at the end; and finally being stuck on the Gothic Line near Bologna, during the horrifically cold winter of 1944 when the Germans pinned the allies—and his division—down for months in the snow. He eventually ending up walking (yes, on foot) from Rome to Turin with his unit while supervising a team of medics, getting awarded the Bronze Star for saving a man’s life during an artillery bombardment, and being promoted to the rank of Major. He is self-deprecating about his Bronze Star (“I don’t quite know why I did it—it was really stupid—running out of that church into the square where a soldier lay wounded, with artillery shells falling left and right, and dragging him inside…”); nearly incredulous that he lived while so many of his fellow soldiers died (“I’m a very lucky man to be alive today”); and proud of his service as a medical officer (“I took the Hippocratic Oath,” he told me once, “and so I never carried a sidearm even though I was required to”). While on the front lines in Italy, he noticed how the constant exposure to combat wore men down, and he wrote and published the seminal article on what is now called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which he entitled, “Old Sergeant’s Syndrome.” 77 years later it is still quoted in psychiatric and sociology textbooks. The article earned my father promotion to the post of“Division Psychiatrist,” the first such appointment in history in the US Army.

He (and my mother) came back safely, as did–thank God– my own son. But many made the ultimate sacrifice and did not return to their loved ones.

A sampling of assorted wisdom I collected from my dad over the years. He was tough on me, to be honest, but he did have some really pithy sayings:

- On preparation: “There is no substitute for genuine lack of preparation.” (This was printed in a book on aphorisms and witty sayings).

- On being careful about whom you mouth off to: “Never talk back to a General. I did, and I lost a cushy job riding a medical supply train in Northern Africa and was sent to live in a foxhole on the Italian front as a Battalion Surgeon” (true story).

- On getting along in a foreign country: “You only need to know a few well-chosen words in a foreign language to get along. The first word I learned in Italian was ‘cipolla’ which means ‘onion.’ As we marched through the Italian countryside we would yell out to the farmers, ‘cipolla?’ and they would give us some onions that we would then chop up and put in our c-rations, which were so bland.”

- On your convictions: “Sometimes you have to act on your convictions. I had tuberculosis in medical school, and so I was classified 4-F by the Army. 4-F is medically unfit for service. I read widely at the time, however, and I understood how evil the Nazis were. I was Jewish, too, which gave me even more reason to serve. So with help from my father, I made contact with the selective service board, and they arranged for me to sign a waiver in order to enlist.”

- On giving people bad news: “If you know you’re going to have to deliver some bad news, tell people as far in advance as possible—this enables them to process it before the actual event. If you’re going to miss a day of work in a month, tell your boss immediately. He may be upset when you tell him, but by the time the day finally rolls around he will have already processed his anger and he’ll be just fine with your day off.”

- On being careful about taking on others head-on: “Never get into a pissing contest with a skunk.”

- On setting aside your worries: “At the battle of Monte Cassino, we were under constant artillery bombardment, and we slept in deep foxholes surrounded by sandbags. If your foxhole took a direct hit during the night, and many did, you would not wake up in the morning. So before going to sleep I would do everything I could to ensure I was as safe as possible: I would rearrange the sandbags, dig a bit deeper into the foxhole, organize my personal belongings, and so on. Then I would stop worrying and go to sleep.”

My mom also served right at the front lines in a mobile surgical unit (as in MASH, the TV series), and she had a similar philosophy about worry. Whenever I was sick with anxiety over something at work, she would say, “You know Andrew, in ten years you aren’t even going to remember what you were in a state about today. It will be forgotten. But what will still matter are the really important things, like your your family and your friends.” Having grown up quite poor, living in a cold water flat in Manhattan in the 1920s, my mom also knew something about inequality–she always told me, “Just remember: The rich get richer, and poor get poorer.” She didn’t need modern economists to tell her about the real and growing barriers to economic mobility today!

Below: My mother, Alma Sobel, in her Army nurses uniform. Her mobile surgical unit followed the D-Day invasion troops from England all the way to the heart of Germany.

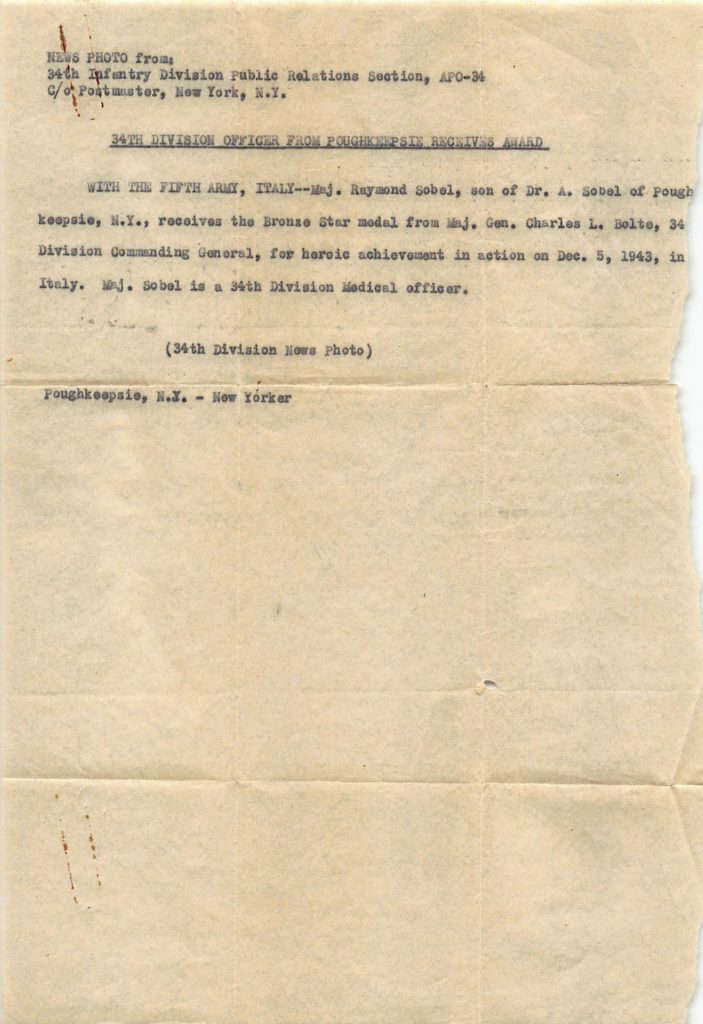

And below her, my father receiving the Bronze Star from his commanding general in early 1944 (the incident was in December 1943).