The One Thing that Kills Personal Learning

Have you ever met someone at an event or party and asked them lots of questions about themselves—and, consequently, learned some interesting things from the conversation? But then, you realized they were utterly incurious about you, and never asked a single thing about yourself? In the end, they learned nothing from the encounter. Their lack of interest in others may have also come across as boorish and self-absorbed.

A strong sense of curiosity, in short, is probably the biggest factor that helps fuel your personal learning. Conversely, a lack of curiosity really kills it.

My wife and I are in Paris for a week. We’ve visited here often, and I’ve come for business a few dozen times. At worst, Paris can be frustrating and some Parisians can be less than friendly to tourists. At its best, it’s one of the world’s most sublime cities, packed with culinary and cultural marvels. But it’s all the same Paris. A big part of the difference is in your perception.

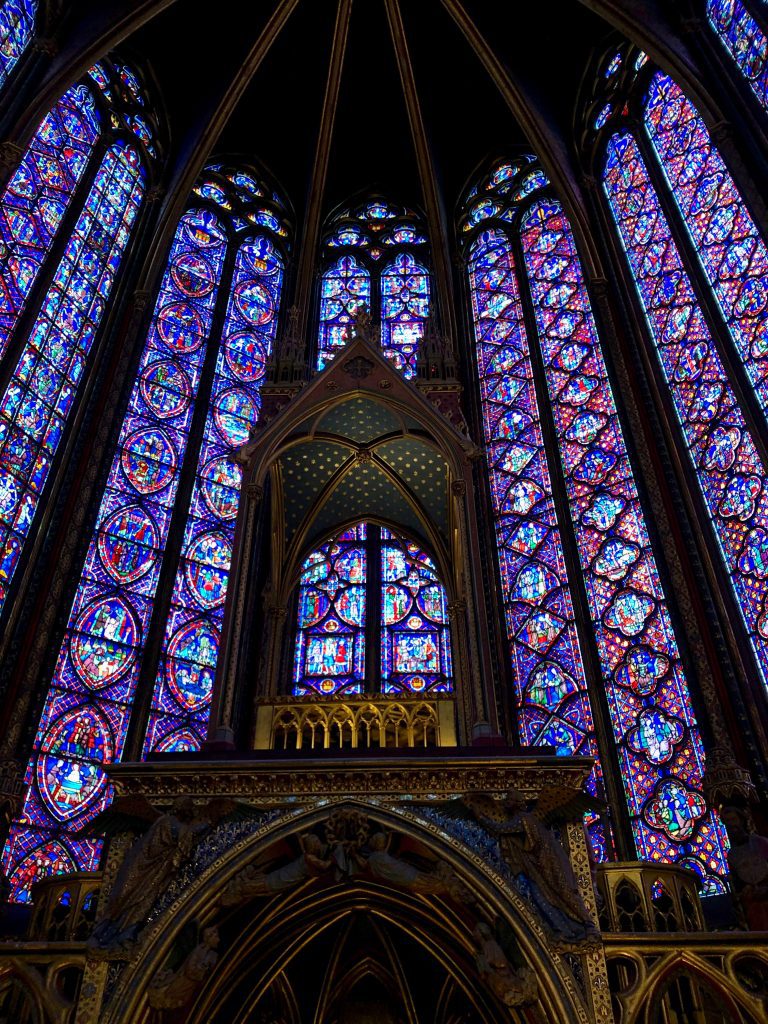

The first morning we arrived from the states, we went to Saint-Chapelle on Île de la Cité. It was built in 1248 as the personal chapel of King Louis IX, and is considered a stunning marvel of gothic architecture. The more than 1100 stained glass window panes take your breath way.

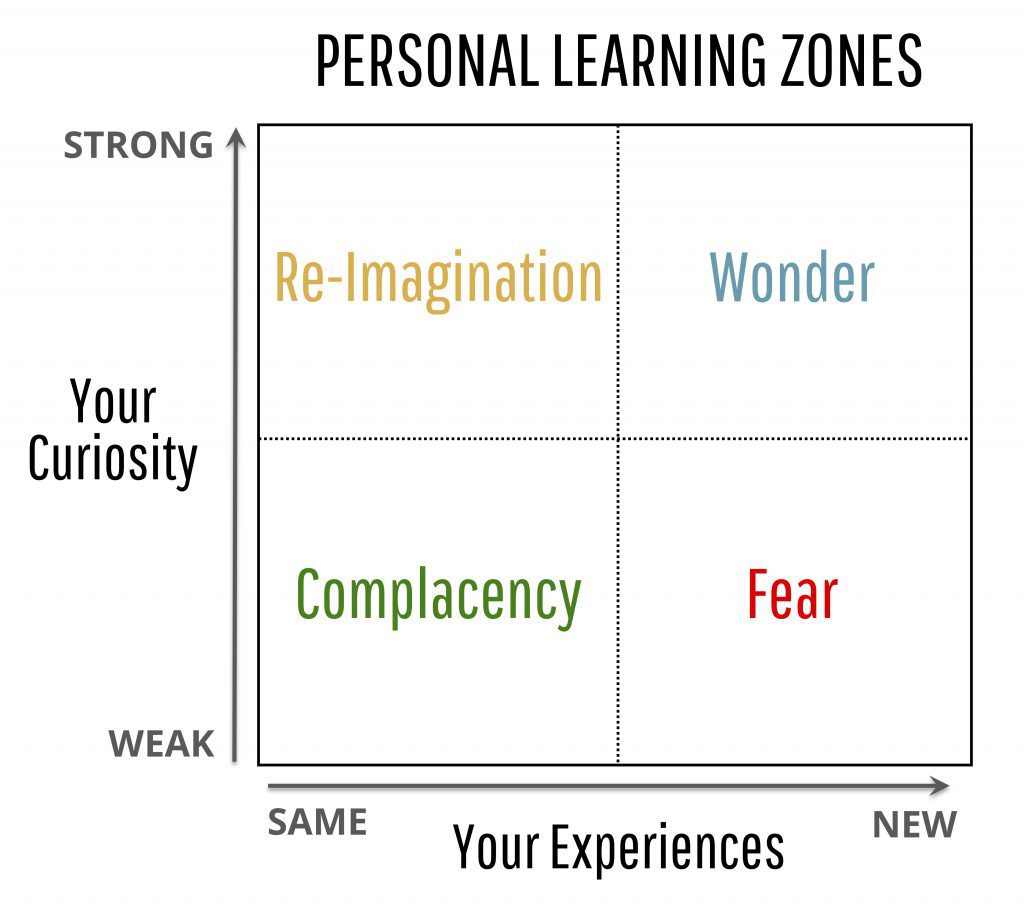

This was our fourth or fifth time seeing the church, but it was nonetheless a new and wondrous experience. You might ask, “why?”—what made it seem new? The graphic, below, explains this:

If you have the same experiences over and over, and are not very curious, you end up going through the motions and becoming inured to the activity. You’re in the Complacency quadrant, where you stop learning. It’s easy to get into this rut at work. We talk about “learning from experience,” but research shows that many people don’t actually learn from experience

If you approach repetitive experiences with curiosity and a belief that there is always something new to discover—which is what happened on our repeat visit to Saint-Chapelle—you enter the upper-left quadrant, Re-Imagination. You may fix the same problem 100 times at work, but if you’re truly curious, each time will be slightly different. You’ll see new things. At Saint-Chapelle, we read up on the dozens of Biblical stories told in the stained glass, and about the laborious process of blowing and staining the glass. We picked out a few panes to study in depth, and saw them with new light (pun intended). We’d been there before, but it felt magical.

When you experience new things with a sharp sense of curiosity—which happens in the upper-right quadrant—the result is a sense of fresh Wonder. At work, for me, it might be confronting a new type of client challenge, or accomplishing something important (e.g., publishing a new book!). I also get that feeling of wonder from new outdoor experiences, like finding myself just 10 feet from a large Peregrine Falcon in Central Park, or watching a deer come up to my office window at our house in Santa Fe and lick it (it happened—I have a video of it).

Finally, when you lack curiosity, the prospect of experiencing new things or meeting new people often engenders Fear (this occurs in the lower-right quadrant). Weak curiosity, in short, makes you either uninterested in or afraid of new experiences.

I’ll let the great scientist Albert Einstein have the last word. He wrote to a friend, “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.”